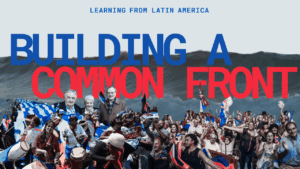

Why this matters

Across Europe, progressive movements and left-wing parties face a familiar challenge: fragmentation. Despite widespread discontent with inequality, climate breakdown, and democratic erosion, the left often struggles to work together. Meanwhile, the right, driven by shared interests, has proven far more compelling at presenting a unified front.

Latin America offers a powerful case study in how diverse movements and parties can build sustainable alliances capable of reshaping society. The Uruguayan Frente Amplio (Common or Broad Front) is one of the most outstanding examples.

As part of the Ulex Project’s new series Learning From Latin America: Building a Common Front, Carol Marín and María Llanos (we) have explored what lessons European movements might draw from Uruguay’s experience. We interviewed activists, party members, and grassroots organisers to open a window into a half-century of experimentation with unity amidst diversity.

What is the Frente Amplio? A short history[1]

The Frente Amplio (FA) was founded in 1971 as a coalition of left-wing parties, unions, and civil society groups. At its core was the recognition that no single organisation could stand up to authoritarian repression or deliver social transformation alone.

Only two years after its creation, Uruguay fell into a military dictatorship (1973–1985). While banned from open politics and persecuted by the authoritarian regime, the FA survived underground, with grassroots networks—often sustained by women—keeping resistance alive.

When democracy returned in 1985, the coalition re-entered political life, gradually building electoral strength. In 2004, the FA won the presidency with Tabaré Vázquez, marking a historic breakthrough. From 2005 to 2020, the FA governed Uruguay for three consecutive terms, delivering significant reforms. The creation of the National Integrated Health System (SNIS), moving Uruguay toward universal coverage; Poverty reduction programs bringing dramatic decline in poverty (estimates reported a fall from ~40% in 2005 to under 9% by 2019), making Uruguay one of the most equal countries in Latin America during that period; The FA economic strategy managed to maintain stability while increasing wages and minimum wage, and strengthening unions and collective bargaining.

Moreover, FA governments created landmark laws on same-sex marriage and regulation of abortion, expanding civil and reproductive rights.

Frente Amplio influence in the region.

The FA long governance (2005–2020, and returning 2025) made it a reference point for other progressive formations in Latin America, influencing policy ideas about social inclusion, public health and more. Their participation has been crucial in transnational left forums (as Pablo Alvarez accounts on Episode 6), sharing strategies for coalition-building and developing regional resistance. The FA amongst the “Pink Tide” governments (Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Uruguay) were crucial to oppose The ALCA, the abusive Free Trade agreement proposed by EEUU for the region. In 2005 the ALCA was refused with the slogan “ALCA, ALCA, al carajo”[2], leading to the emergence of numerous regional agreements.

The Frente Amplio lost the 2019/2020 election after 15 years in power.

After this loss the FA undertook a humble, thorough and critical process to reflect on the election results. The “proceso de escucha” (listening process), involved party leaders and militants touring the country to hear directly from citizens about their frustrations, challenges and priorities. Through these processes the FA rebuilt trust, revitalised the party from its bases and its leadership, and repositioned itself as a responsive, reliable and relevant movement. This was a significant contribution in securing its return to government in 2025.

Key learnings from the Frente Amplio.

The following represent key insights that Carol and I have drawn from the series of interviews, which are further elaborated in the introduction. We see these reflections as highly relevant for the European context.

The Frente Amplio’s capacity to remain a durable coalition owes much to its embrace of ideological diversity. Despite differences between communists, anarchists, social democrats, feminists, christian leftists, and grassroots movements, the FA has always centred common purpose (democracy, social justice, equality) over ideological purity. Margarita Percovich recalls how during the dictatorship, broad alliances continued to be forged — “working collectively with members of all political parties, sharing information, letters and recordings and resistance” even in such a dangerous context. “This helped keep democracy alive” (Episode 2). This tradition of comradery is part of the Uruguayan DNA and central to FA’s culture, and the commitment to keep it alive and well throughout the years, translates into mechanisms that ensure all sectors feel heard, and a culture of tolerating internal tensions.

“How do we make decisions amidst differences? How do we honour grassroots participation? How do we enact values such as empathy, patience, and generosity so that they are not only stated but also central to political practice?”

Rather than treating values as static guiding ideas, the Frente Amplio has institutionalised them. Grassroots participation is not rhetorical: more than 500 local committees (comités de base) across Uruguay are linked through a system of delegates feeding into national plenaries. This ensures direct citizen input into the political programme and agenda, keeping the coalition grounded in everyday concerns.

Decision-making is not binary; it is layered. First, there are areas of shared consensus; second, negotiated paths for managing differences; third, the recognition that some disagreements are irreconcilable, yet must be worked around rather than ignored. This approach allows progress without erasing diversity. As Margarita Percovich notes, these structures and processes have been critical for embedding feminist perspectives into the FA’s programme — including the adoption of gender parity in party statutes and the introduction of quota laws (Episode 2).

The downside of this model is that consensus-building can dilute more radical proposals, slowing the pace of transformative change and sometimes producing platforms that appear overly cautious. A common phrase captures this ambivalence: “El Frente Amplio tiene más de amplio que de frente” (“The Broad Front is more broad than it is a front.”) — suggesting that its breadth sometimes weakens its capacity to project a coherent, bold left agenda.

As explained above, after losing the 2019 election, the FA embarked on a process of collective listening and dialogue, gathering feedback across the country. This showed one of the FA’s strongest traits: humility in leadership and treating mistakes as opportunities to deepen connection with wider society.

The public listening process (“proceso de escucha”) was not superficial — the FA opened spaces for citizens at every level to voice reflections, frustrations and priorities. This feedback fed directly into the programme’s development and its messaging, the candidate selection, and the overall strategy. Such listening helped re-establish trust with sectors that felt neglected or disillusioned. Both Ricardo Ehrlich and Margarita Percovich underline the importance and difficulties that this process entailed (Episode 1 and 2). This humility is an extension of a long tradition: Percovich remarks that “Lo importante es tratar de construir actores lo más potentes posibles para negociar con los actores que deciden en los Estados” (“What’s important is to try to create the strongest possible actors to negotiate with those who make decisions in the State”).

4. The state as a tool

Former president José “Pepe” Mujica famously compared the state to a hammer: “Con el martillo o bien puedes clavar un clavo o puedes darte de martillazos en la cabeza” (“With the hammer, you can either drive a nail or you can smash your own head with it”) . The Hammer can build or destroy depending on who wields it.

While maintaining close ties with social movements, the Frente Amplio has shown how institutions can be more than bureaucracy — rather powerful instruments of transformation when populated by people committed to redistributive, feminist, and ecological values-. Instead of rejecting the state, the FA has used it to enact structural reforms while consistently trying to sustain connections with movements avoiding top-down management.

Margarita underlines that this requires an active tríada (triad) — the integration of social movements, political parties, and academia — to generate both pressure from below and evidence-based arguments for reform (Episode 2).

Others in the interviews also echoed this understanding of the state as a contested but usable tool. Romina Redesca describes the comités de base as “escuelas de ciudadanía” (“schools of citizenship”) where ordinary people learn to engage institutions while shaping political agendas (Episode 3). Eduardo Alonso adds that FA’s participatory infrastructure makes the state “un espacio de disputa” (“a space of contestation”) rather than something distant or untouchable. Andrea Apolaro (Episode 5), reflecting on the Redes Frenteamplistas, highlights how innovation and independent civic networks help institutions remain open: “las redes permiten que el Estado no se quede encerrado en sí mismo” (“the networks prevent the state from closing in on itself”).

FA experience is not about blind trust in institutions, but about actively reshaping them through organised citizen participation and the permanent dialogue between state and society.

For me (María), one of the most powerful lessons in this series is how memory and narrative are central to political culture in the Frente Amplio. The FA’s history of resistance — against the dictatorship and the experience of taking political power through collaboration and solidarity— continues to fuel its unity today. From the years of activism and followed by authoritarian repression, exile, and eventually victory at the ballot box, members have carried stories that sustain a shared sense of purpose. As Margarita Percovich mentions “las mujeres en concreto, conservamos la llama de la democracia en el interior de las familias” (“Women particularly kept alive the flame of democracy at the heart through our families”) when many men were imprisoned, disappeared, or exiled (Episode 2). This lived memory is not just part of history but a moral reservoir — a source of identity, resilience, and political imagination.

Other voices in the series underline how remembrance continues to shape collective action. Eduardo explains that the comités de base themselves are products of this history, created in the 1970s as spaces of resistance and later reactivated to keep alive traditions of grassroots deliberation. Andrea emphasises that intergenerational storytelling within the FA helps newer activists connect their struggles for feminism, ecology, and civil rights with the older legacies of anti-dictatorship solidarity. Romina frames memory as a tool of empowerment: “recordar es también proyectar” (“to remember is also to project”), a way of reclaiming imagination for future struggles.

The FA’s experience suggests that fostering narrative memory (through storytelling, culture, and public remembrance) can act as a hopeful pillar to rebuild collective vision.

Moreover the use of Radical Imagination — not abstract utopias, but concrete alternatives grounded in lived possibility — remains one of the FA’s enduring strengths. As Carol reflects, “Too often our activism is shaped by defeatism and pessimism… The FA shows how radical imagination and concrete utopias are important and have a role in breaking through neoliberal hegemony.”

Why this is relevant for Europe today

The European left faces a landscape marked by fragmentation, electoral decline, and the rise of far-right populism. The challenges—climate crisis, economic inequality, migration, democratic erosion—demand coordinated, large-scale responses.

The experience and example of the Frente Amplio, amongst others in Europe, can offer concrete learnings on how to build coalitions and alliances across differences; how to enable grassroots participation and create strong structures and processes to sustain distributed decision making and citizens voice central; and the importance of sustaining a culture of empathy and imagination to enact visionary politics.

As Mujica once said, “While the left are divided by ideas, the right are united by interests.” If Europe’s progressive forces want to mount an effective challenge, we will need to rediscover how to forge a common front.

Looking ahead

The Learning From Latin America series features six interviews with activists and leaders such as Margarita Percovich (feminist pioneer), Ricardo Ehrlich (longtime FA activist), Pablo Álvarez (international strategist), and grassroots organisers Andrea Apolaro, Romina Redesca, and Eduardo Alonso. Their stories bring to life the values, structures, struggles, and creativity that have sustained the Frente Amplio for over five decades.

Our hope is that this series will spark further dialogue across Europe: we aim to host online webinars, roundtables and eventually in-person workshops where participants can reflect, develop skills, practices and knowledge on how FA’s lessons, amongst others, might translate into our own contexts. In the longer term, we envision a community of people diving into the practice of building and sustaining broad coalitions and alliances.

The series is available on the Ulex Project website and on YouTube, with Spanish audio and English subtitles. If you would like further information about upcoming events or opportunities to take part, please contact us at carol@ulexproject.org.

***

[1] Ricardo Ehrlich in Episode 1 describes in detail the FA´s history

[2] “Chávez confirmed his presence at the Summit of the Americas … and expressed that the summit “dará la oportunidad de mandar ‘al carajo’ la propuesta de libre comercio que impulsa Estados Unidos.” (“[It] will give us the opportunity to send to hell the free trade proposal pushed by the United States.” El País (Uruguay), 28 October 2005.

María Llanos del Corral specialised in complexity and participation applied to organisations. Her main work as a facilitator and consultant focuses on organisational change, emergent strategy, leadership and culture that is responsive to complex, changeable and uncertain environments.

She is the Co-founder of Eroles Project, a learning-for-action centre, and La Bolina, a regeneration initiative combining refugee inclusion, agroecology and rural repopulation. María also collaborates long-term with the Ulex Project, co-leading courses such as Ecology of Social Movements, Integral Activist Training and Movement Learning Catalyst; And together with Carol is developing the project “Learnings From Latino America: Building a Common Front”.

She has co-authored several publications, including: Movement Learning Catalyst: A guide to Learning for Systemic Change. Enfoques y herramientas participativas en la cooperación al desarrollo, Small is Important: Learnings from an integration and regeneration Project

Carol Marin Alvarez comes from a family where politics was the passion of everyday life; anarchism, communism, and republicanism blended harmoniously because the goal was clear: the emancipation of the people. She studied Philosophy and completed a postgraduate degree in Humanities. Her intellectual interests turned toward poetry for its power to create new worlds.

She has co-founded two prefigurative projects, Ecodharma and the Ulex Project. Apart from sustaining the functionality of the organization, Carol has been closely involved in the Movement Learning Catalyst Project and its developing work rooted in the learning traditions of Latin America, where some of the most subversive practices of Radical Democracy take place. At present, her passion lies in studying the power of concrete utopias and critical theories, seeking to recover the impulse of hope as a driving force in history.